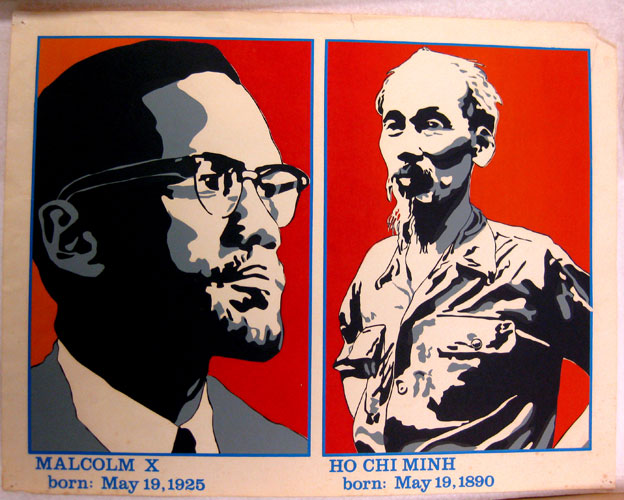

We of course accept only the former definitions for both of these historical figures. At no time in history has U.S. imperialism ever acknowledged its exploitative role throughout the world so there is no existing scenario where imperialism is ever going to accept and respect those people who dared wage a fight against its hegemony. So, Malcolm and Uncle Ho are strong examples of forward progress for us and we would like to take this space on the day each of them was brought into this life to acknowledge the little discussed connections between each of their massive contributions to humanity.

As we have discussed previously, Ho Chi Minh was a student at Columbia University in New York City during the late teens and early 20s of the last century. Living in Harlem, New York, U.S., and working as a dishwasher at local restaurants, Uncle Ho experienced extreme poverty and life in the inner city of the U.S. He wrote about how he relished going to the street corner rallies and listening to African nationalist speakers address the problems of African people worldwide. Uncle Ho discussed how his favorite speaker was the Honorable Marcus Mosiah Garvey who at that time was laying the groundwork for his Universal Negro Improvement Association which went on to become the largest independent African organization our people have ever had. Garvey's nationalist message had a huge impact on Uncle Ho. The message helped him frame his perspective on white supremacy within the U.S. A perspective he would go on to use in a tactical sense in the war against U.S. imperialism. He would exploit the disconnect between Africans, even those in the U.S. military, and the U.S. government to spread the seeds of distrust and demoralization about fighting in a war, for a country - the U.S. - that did not recognize and/or treat us like human beings. Even imperialist analysts are forced to acknowledge that this psychological attack challenging the relationship between Africans in the military, and the contradictions of a racist U.S. government, had a profound impact on the morale of U.S. troops, thus playing a significant role in the U.S.'s inability to advance to victory against the Vietnamese people.

Garvey's message was equally influential to the family of Malcolm X. Malcolm's mother was born and raised in the Caribbean like Garvey so Louise Little had no trouble understanding the Pan-African message Garvey was delivering. Earl Little, Malcolm's father, was a staunch and dedicated Garveyist who, along with the support of his wife, did much work to spread Garvey's message during Malcolm's youth. The message of African nationalism and Pan-Africanism flowed through Uncle Ho and Malcolm as each developed into their life paths which would lead them to achieve their ultimate contributions.

There is much being discussed today about Malcolm's final year of life. The debate is focused primarily on whether Malcolm wanted back in the Nation of Islam or not. Any critical observer would know immediately that based on Malcolm's behavior, this objective was not central to the development he was engaged in. He wrote in his autobiography that the highest honor of his life was his time spent with Kwame Nkrumah, the first president of Ghana, the founder of the Convention People's Party, and the founder of the All African People's Revolutionary Party. Its strange that Malcolm would make such a strong statement like this about Nkrumah, but no scholar has ever attempted to examine what he meant deeper. In fact, most scholars like Manning Marable are so intent upon connecting the finances for Malcolm's travels to the reactionary (so-called) Muslim leaders of Saudi Arabia that virtually no attention is given to the work Malcolm was doing in that final year and what his developing relationship with Nkrumah actually was. Malcolm nor Nkrumah spoke at all about their well publicized two or three meetings. Actually, besides Malcolm's statement about the highest honor and Nkrumah's pronouncements in his letters to others about how fond and respectful he was of Malcolm's abilities, nothing else was really mentioned by the two of them. What we do know is shortly after returning to the U.S. from meeting with Nkrumah, Malcolm named his newly founded political organization the Organization of Afro-American Unity after Nkrumah's Organization of African Unity. And, although there's no question that Malcolm's speeches going back as far as 1960, clearly demonstrated a political line that was diverging from that of the Nation of Islam, his speeches during that last year had a much more pronounced Pan-African framework within them. The key to all of this is Malcolm's African nationalism was being shaped by his developing relationships with Pan African revolutionaries like Nkrumah. And, Nkrumah's understanding was enhanced greatly by his understanding of Garvey's ideas. Nkrumah called Garvey one of the key influences in his life and he honored Garvey by placing the Black Star, the emblem of Garvey's Black Star Ships company, on the Ghanaian flag.

Further influenced by revolutionary Pan-Africanists like Nkrumah and Sekou Ture, Malcolm came back in 1964 with a vehement anti-imperialist message. And, central to that message was a strong sentiment against developing U.S. imperialist aspirations in Southeast Asia. This is made clear by Malcolm's reference during his famous "The Ballot or the Bullet" speech in March of 1964 where he encourages Africans to support "that little man in Asia" who was picking up the gun and standing up "to uncle sam!"

Malcolm, of course was assassinated by U.S. imperialism on February 21, 1965, (if you are running around here saying ridiculous things like Louis Farrakhan killed Malcolm, you are doing police work for free), but the continued tie between Malcolm and Ho Chi Minh, influenced heavily by the work of the Garvey movement, had one more card to play. In 1967, two years after the silencing of Malcolm's voice, a young Stokely Carmichael - two years before he would move to Africa and become Kwame Nkrumah's political secretary in helping build the All African People's Revolutionary Party at Nkrumah's request - would seek out counsel from Uncle Ho Chi Minh. Young Carmichael, then the Prime Minister of the Black Panther party and the just removed chairperson of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) where he helped guide SNCC into becoming one the movement leaders of the emerging Black Power movement, had the desire to contemplate what best represented his ability to make his best contribution. Hounded by challenges within the Black Panther Party, which we know now were largely instigated by imperialist forces, young Carmichael sought lunch with Ho Chi MInh to ask him his thoughts on how young Carmichael should proceed in his work. Sitting at an outside table in the midst of his country fighting for its life against invading U.S. imperialist forces, Uncle Ho calmly advised the young Carmiahel to acknowledge that he was African and to accept that the answers to the questions he had would be most logically answered by returning home to Africa. Young Carmichael considered that conversation a confirmation of what he had been thinking already. He ended up living in Conakry, Guinea, West Africa, becoming Nkrumah's secretary and an aide to Sekou Ture, becoming a leading organizer in Ture's Democratic Party of Guinea along with the All African People's Revolutionary Party, and changing his name to Kwame Ture in 1977 to honor the work of Nkrumah and Sekou Ture.

Today, we honor Malcolm and Ho Chi Minh not just because of their born days. We recognize that a person's legacy isn't built around when they are born since we have no control over when that happens. Your legacy is built around what you do while you are alive. Although Malcolm and Ho Chi Minh never met one another, we know that their legacy and mutual respect for one another is cemented in history. Both courageously decided to dedicate their lives to fighting imperialism. The valiant struggle of the Vietnamese people was an inspiration to Malcolm as he expressed openly. The struggle of the African liberation movement around the world was also a major inspiration for Ho Chi Minh which he clearly articulated. Now, with both major legacies firmly intact, its simply up to us to build on those bodies of work to further our struggle to advance humanity.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed