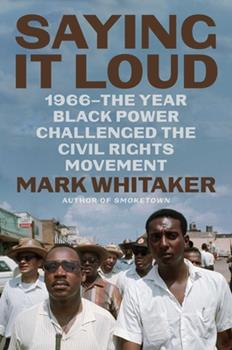

Whitaker’s book, focusing on the events that exploded out of the June 1966 Mississippi march where the Black power chant started a new phase of the civil rights movement, had a specific focus on Kwame Ture, formally Stokely Carmichael. After his work in the U.S. movement, Ture played a significant role in laying the foundation for the work of the All African People’s Revolutionary Party (A-APRP), the party I have spent my entire adult life contributing to, so I knew I had to study this book. Doing so is a priority because there has been a concerted effort, unnoticed by the untrained eye, directed at discrediting the work of uncompromising radicals like Kwame Ture. Former U.S. empire president Bill Clinton, speaking at former civil rights activist and U.S. congressman John Lewis’s funeral in 2020, provided an example of this trend when he took a swipe at Kwame’s legacy within the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

It is without question, our responsibility as African revolutionaries to protect the legacy of our soldiers so that our people can know that its perfectly okay for us to decide to chart a of action that isn’t in any way defined by capitalist norms and values. Consequently, I immediately pre-ordered Whitaker’s book in November of 2022, and the book arrived on February 7, 2023. A 307 page book, I completed it by Saturday, February 10, 2023. And, I don’t say that to brag, but to illustrate how frustrating the contents of the book were and how determined I was to get through it so I could use our platforms to let people know. As is the case within the capitalist paradigm of history, Whitaker’s book made every effort to discredit Kwame Ture as is their practice with anyone who exhibits genuine African militancy that doesn’t cow tow to worldwide imperialism.

We will say first that you are strongly encouraged here to read the book. We will always encourage people to read everything, regardless of how bad, because we believe one of the primary reasons poor works like Whitaker’s book are able to continue to pass as major literature on our movement is because the overwhelming majority of us have made little to no effort to take it upon ourselves to seriously study and articulate our history for ourselves. And by ourselves, I don’t mean anyone with “Black” skin. We recognize the necessity at all times for a nation, class, gender analysis in anything we study and use so we are talking about a revolutionary Pan-Africanist perspective, not the race of the author.

“Saying It Loud” fell short by using tired old tropes about the civil rights movement being the highest expression of African existence while the Black Power era of that movement is depicted as poisoning the sanctity and pureness of the anti-segregation phase of the movement. And, as can be expected, Kwame Ture’s rise to chair of SNCC was consistently portrayed in the book as the demise of the organization while John Lewis’s tenure was discussed, as is usually the case in reformist literature, as pristine and without major contradiction.

The above would actually be okay, because there are always going to be serious ideological differences between the revolutionary and reformist perspectives of history. This is to be expected, but what’s offensive about Whitaker’s book is its efforts to minimize the intellectual capacity and seriousness Kwame Ture had for our struggle. The author constantly paints a picture of Ture as never truly being serious about the struggle as if Kwame’s style and practice during the most dangerous periods of the movement provide some sort of evidence about his lack of seriousness and even worse, his lack of mental stability. For example, Whitaker saw Kwame’s use of humor while being incarcerated at the notorious Parchmen Prison in Mississippi, for his civil rights work as proof of his lack of seriousness. Whitaker insinuates the same regarding Kwame’s reaction to a number of terrorist events that Kwame was directly involved in. Anyone who knows anything about the torture and degradation Kwame and others experienced routinely, knows that any method the organizers could use to get through, and help others get through, the experience, should be praised, whether you understand those tactics or not. This is true because regardless of how people processed that trauma, they were there because of their courage and commitment to our struggle for justice. Kwame’s willingness to consistently risk his life had no personal upside. He never cashed in on those experiences such as could be argued about a number of his political contemporaries. This fact can never be questioned, especially by someone in the media who never risked a toenail for anything beyond themselves.

Unfortunately, Whitaker continues with this logic throughout the book, criticizing everything Kwame does without even the slightest analysis applied in the process. For instance, he focuses a lot on Kwame’s individual speaking engagements as if to imply that Kwame was only interested in the spotlight that the SNCC chair position afforded him and not movement building. This point is further brought out in the book by Whitaker’s insistence that Kwame’s speeches were “incendiary” and that he never explained what was meant by Black Power. To Whitaker, incendiary apparently means anything that doesn’t fit neatly within the capitalist paradigm. For instance, Kwame’s insistence that African people should use whatever means are available to them to secure their human rights is incendiary to Whitaker because we are never supposed to have agency and humanity. We are always only supposed to accept what the capitalist system is willing to provide to us. In this colonialist/slave master framework, any suggestion that we should take our freedom from an empire that has everything it has solely because of what it steals from us, is always considered ill responsible. As to Whitaker’s criticism about Kwame’s refusal to define Black Power for the U.S. capitalist media, its incredible that he cannot understand that a major underpinning of Black Power is the concept that we will determine our own destiny. A major element of that self determination is recognizing that we no longer need to base our movement on what is understood by the people holding up the system that is oppressing us. If you want to understand Black Power or Pan-Africanism, etc., do your own emotional labor and study to understand it. It is not the responsibility of the oppressed segment to define their vision in a way that makes sense to you and its unfathomable that this still needs to be explained to people in 2023. And, to add insult to injury, Whitaker suggests that Kwame’s reaction to the military draft board and some of his responses to the frantic pressure within SNCC, suggest mental instability on his part. This worthless analysis isn’t even worth the time it would take to respond to it.

Finally, the book relies on more tired and played out tactics of disrespect such as refusing to acknowledge that Stokely Carmichael becomes Kwame Ture in 1977. Although Whitaker articulates the name change, he continues to refer to Kwame as Stokely Carmichael, a fundamental and basic form of disrespect not just for Kwame, but for our efforts to de-colonize ourselves as a people. Also, this book falls into the exact same bourgeoisie trap that Peniel Joseph’s work on Kwame’s life and so many other depictions of Kwame’s life after he leaves the U.S. for good in 1969. Since these people wholeheartedly accept the bourgeoisie and racist conception that everything is always centered around the U.S., anyone like Kwame Ture who decides otherwise must be insane and this is the basis from Whitaker and so many others reference to Kwame’s decision to move to Africa. Relying on the same discredited allegations against Sekou Ture and the Democratic Party of Guinea, Whitaker uses Kwame Ture’s move to Guinea-Conakry to again question his intellectual stability while relegating any further analysis of Kwame’s work to his annual appearances in the U.S. (since for these people that’s the definition of anything and everything).

This sad analysis of Kwame’s life completely ignores his work from 1969 to 1998 to become a Central Committee member for the Democratic Party of Guinea and the A-APRP while using his contacts and influence to expand the A-APRP throughout Africa as called for in Kwame Nkrumah’s “Handbook of Revolutionary Warfare”, the strategy to achieve Pan-Africanism. After just returning from Guinea-Bissau a few short weeks ago, I was able to again see the results of Kwame Ture’s initial work in Africa in building the A-APRP and Pan-Africanism as I’ve seen in previous trips to Ghana, Tanzania, Gambia, Senegal, etc. Even a cursory observation of this massive body of work reveals that Kwame Ture retained consistency in elevating his relation to Black Power to a broader and more comprehensive understanding of Pan-Africanism, the highest expression of Black Power the world knows. This elevation was progress from Kwame Ture, not evidence of an eroding mental state. Its hard to imagine a more racist and reactionary framework as that suggested in Whitaker’s book around this question, no matter who or where it originates from.

So, again, we encourage you to read Whitaker’s book if you desire to do so. We also encourage you to study up on the work of the A-APRP, particularly Kwame Ture’s life after he moved to Africa. We encourage this because its ill refutable that the more we practice this type of study, the easier it becomes for us to interpret these things through the critical vision necessary to have the healthiest perspective humanly possible. Things like acknowledging that this period Whitaker covers in his book represents a period when Kwame Ture was a mere 25 years old facing opposition from every corner of the capitalist power structure. Imagine a 25 year old speaking to the contradiction of a powerless and oppressed people coming to see their agency as being their responsibility and truly justice minded people rising to support that concept instead of acting as if such a perspective could only exist among people who have some other ulterior motive and/or or are just not truly serious about their messaging. Pay attention to how if Whitaker provided a fraction of critique towards notoriously corrupt and racist individuals like Ronald Reagan and Federal Bureau of Investigation terrorists Cartha Deloach and William Sullivan (he barely mentions them) that he did Kwame Ture he would have had a 1000 page book.

We realize that imperialism’s role is always going to be to discredit any efforts by anyone to challenge its hegemony. We will never be taken aback by that. What we are concerned about is just how easy it continues to be for so many of us to be led astray by their continued dirty tricks.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed