I admit fully that as soon as I heard about Peniel Joseph’s biography on the late Kwame Ture entitled “Stokely – A Life” I was skeptical. I felt that way for a few reasons, none of them new, as it relates to scholarship on the life of Kwame Ture, formally Stokely Carmichael. I think it’s fair to say the bibliography of Kwame’s life repeatedly plays up the approximately seven years he spent within the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (pronounced SNICK), and the one year he spent within the Black Panther Party (BPP), while down playing, or even ignoring, his last 30 years living in Africa as an organizer for the All African People’s Revolutionary Party (A-APRP). The focus on the 60s is somewhat understandable due to the relative lack of attention paid to the bold work carried out by Kwame and other SNCC, Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), and Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) organizers in the south. Kwame, when he was known as Stokely Carmichael, played a major role throughout the civil rights and Black Power movements, something even Malcolm X and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr did not do. So it is indeed logical that Joseph, and other scholars, would spend time wanting to retell the story of Kwame’s contributions to SNCC and the BPP. In fact, Joseph does better than most at relaying a narrative of how Kwame’s organizing skills developed, expanded, and intensified. “Stokely – A Life” does a great job of demonstrating the intellect, selflessness, commitment, and absolute courage that characterized Kwame’s work in the south during those years. For this contribution, we thank Joseph, especially for the vivid way in which he conveys the extent to which Kwame was demonized by the U.S. power structure during the latter 1960s. Joseph’s argues that impactful racist politicians like Ronald Reagan, Richard Nixon, and Spiro Agnew, owed their political advancement in large part to Kwame’s existence and articulation of the Black Power concept – a phenomenon that frightened white America more than 9/11 could ever imagine. This realization is a moving testimony to the incredible burden carried by a mere twenty four year old Stokely at that time. Joseph also skillfully exposes how the first African (Black) Senator since reconstruction – Edward Brooke – won his election in 1966 by specifically using the slogan “a vote against me is a vote for Stokely Carmichael.” The reader is magically transported into a time when Kwame literally commanded such a level of national focus that legislative ideas focused around repressive measures were being named after him. This is a magnitude of attention that escaped even Malcolm X, the man considered the true spokesperson for Black Nationalism and Pan-Africanism in the U.S. during the 60s. Plus, the fact that Joseph produces a clear visual that Kwame never wavered in his militancy and commitment to an independent African agenda does more to honor Kwame’s 60s legacy than pretty much anything else written about his life during that period.

Still, the unique and powerful narrative Joseph carefully crafts up to 1968 diminishes quickly when he is faced with having to address Kwame’s move to Guinea-Conakry, West Africa in 1969. In fact, “Stokely – A Life” is so lean after 1968 that the book would have served a better purpose by stopping there to become a tribute to Kwame’s U.S. work alone. This is true because faster than the average African will switch off a country western song, Joseph’s book evaporates when confronted with dealing with Kwame’s Africa work. Actually, Joseph never actually addresses any of the work Kwame does in Africa. It’s almost as if Kwame did all this courageous work in the U.S. during the 60s before grinding down to a serious halt when he moves to Africa. Then, his contribution is portrayed as consisting simply of giving academic speeches on U.S. college campuses and other symbolic actions until his death. This is an old and tired replay of the same history being written about Kwame’s legacy once he leaves the U.S. for Africa. It’s an easier route for Joseph because it feeds into the same backward and corrupt school of thought that the U.S. is the center of the world struggle for human rights and dignity. This approach also permits the author to avoid having to research, analyze, and critically assess the value of Stokely Carmichael after he moves to Africa and becomes Kwame Ture. This analysis wouldn’t have been easy, but had Joseph attempted to go there, his work would have deepened to a level nothing previously written about Kwame has ever come close to achieving. Since Joseph ends up taking the same common route most historians have taken on Kwame’s life and contributions (after moving to Africa) this biography turns out to be nothing more than a brush fire – the analogy anyone familiar with Kwame knew he was fond of using to define the type of organizer who is active for a moment, but then burns out. Consequently, Joseph misses several key points in understanding Kwame’s thinking and action after moving to Africa. For instance, Joseph makes the point of questioning why Kwame would decide to stay in Conakry and take up the battle as defined by Kwame Nkrumah, but without analyzing Nkrumah’s ideas, Joseph lacks an understanding of the young Stokely Carmichael’s thinking and the older, wiser, Kwame Ture’s resolve. Unfortunately, Joseph has a lot of company in misunderstanding this important link between Kwame Nkrumah, Seku Ture, and Kwame Ture. Instead of seriously investigating that link, he casually dismisses it as a case of cult of personality. Then, Joseph continues down this path by presenting the tired and sadly misinformed assessment and analysis of Seku Ture’s administration in Guinea. In doing so, Joseph simply repeats the same tired rhetoric that Seku Ture was a dictator and Kwame Ture was a quiet co-conspirator to the senior Ture’s corruption.

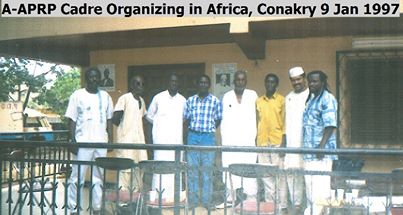

It’s difficult to understand why there is such a consistent lack of intellectual integrity in assessing Kwame’s 30 years in Africa. It’s almost as if there is a conspiracy to actively avoid engaging in the proper research required to dissect Kwame’s legacy in Africa. It would be simple to illustrate for readers why Kwame chose to study under Nkrumah and Seku Ture. It is equally plausible to present an analysis that explains why Kwame decided to dedicate his life to their vision. Joseph could have accomplished this had he taken the time to study Nkrumah’s “Handbook of Revolutionary Warfare” with the respect it deserves. Unfortunately, Joseph apparently didn’t judge Nkrumah’s landmark “Handbook” worthy of time and mention beyond just stating that Kwame Ture read it in one night. Maybe if Joseph had taken the time to seriously study the “Handbook” he would have learned that this book contained a detailed analysis and strategy for achieving revolutionary Pan-Africanism – or one unified socialist Africa as defined by Nkrumah. He would have realized that this strategy came about as a result of Nkrumah’s experience founding the Organization of African Unity (the OAU which today is the African Union), having the practical applications of building Ghana, supporting the radical “Casablanca” Union with Guinea and Mali, experiencing the CIA inspired disaster in the Congo, and being victimized by the CIA-inspired coup that overthrew his government in Ghana. This groundswell of experience gave Nkrumah the qualifications to speak out against the evils of neo-colonialism and imperialism. He was also primed to learn from the mistakes of the OAU and devise a strategy that would build a grassroots revolutionary Pan-African movement. Its common knowledge now that imperialism exploited many of the class and cultural issues that Joseph defines as “shortcomings” to sabotage Nkrumah’s revolutionary actions. What’s not as widely known is the “Handbook” was Nkrumah’s answer to those experiences. Since Joseph makes it clear that the young Stokely Carmichael was searching for direction in 1968, it’s astounding that he and other scholars wouldn’t show more interest in exploring what young Stokely found in that handbook that shaped and characterized his work for the next 30 years. Did Joseph take this route to purposely sabotage Kwame Ture’s legacy in Africa or was this lack of focus simply intellectual laziness? We don’t know, but based on the detail Joseph places on Kwame’s work in the U.S., it just seemed logical that he would extend the same focus to finding out what Kwame established in Conakry once moving there. What we know is there was no A-APRP anywhere when Stokely Carmichael arrived in Conakry in 1969. Joseph neglects mentioning it, but the very first A-APRP work study circle consisted of Nkrumah, Kwame Ture, Amilcar Cabral, and Lamin Jangha (a student from Gambia). This group started meeting in 1969 once Kwame Ture moved to Conakry. The purpose of the work study process is to serve as an organizing unit that spreads the revolutionary political message of one unified socialist Africa throughout the African world. So, in fast forwarding through the 30 year span of Kwame’s work in Guinea, the A-APRP evolved from one work study circle in Conakry in 1969, to 2014, where A-APRP cadre have touched the ground in Conakry, Guinea-Bissau, Sierra Leone, Ghana, Senegal, Gambia, Kenya, Zimbabwe, Tanzania, Azania-South Africa, Britain, France, Germany, Canada, the Virgin Islands, Jamaica, Brazil, and the U.S. These organizers are working tirelessly to create a revolutionary Pan-African consciousness among the masses that anyone who pays attention can see is starting to take hold. The groundwork is being laid for the type of worldwide revolutionary African consciousness that will one day bring Pan-Africanism much closer to our grasp than it appears to Joseph right now. The work to create this reality is exactly the type of daily organizer work that Joseph praises Kwame so handsomely for engaging in during the 60s. This is the same work that elevated Kwame from a U.S. activist into a central committee member for the Democratic Party of Guinea (PDG), along with becoming responsible for organizing hundreds of thousands of youth throughout the country. It was from this capacity that Kwame developed and guided A-APRP cadre into similar positions for Pan-African parties in Guinea-Bissau, Sierra Leone, Ghana, etc. Kwame Ture continued with this work, not just in Guinea, not just in Africa, but in dozens of countries inside and outside of the African continent. Nkrumah’s primary message in the “Handbook’s” is the need to unite all independent revolutionary Pan-African political parties into one continental political party named the A-APRP. Kwame’s effort to coordinate and unite the work going on in all the countries mentioned above was the key to understanding what he was doing in Africa from 1969 to 1998. To not even give cursory mention to all of this monumental work is a sincere shame. And to dismiss Kwame’s commitment to organizing in Africa as simply paranoia at being persecuted by U.S. imperialism is tragically juvenile and reeks of dishonesty. A proper assessment of Kwame’s impact in Africa is to assess that his physical body hasn’t walked the Earth in 15 years, yet the A-APRP still continues to build a Pan-African reality. In 2014, any African movement or leader who wishes to be taken seriously by his people must pay lip service not just to some abstract version of Pan-Africanism, but to the precise vision articulated by Kwame Nkrumah. Robert Mugabe, who was recently elected to an executive position within the African Union, talks all the time about “Nkrumah’s vision for Africa.” Muammar Qaddafi’s push to create one Pan-African currency called the dinar – that would be backed by Libyan gold – was advanced with constant references to Nkrumah’s vision. It would be virtually impossible to find any sensible African, on the continent or not, who would not agree that a Pan-African currency is something Africa desperately needs. And, it isn’t an uncommon belief that it was Qaddafi’s push for this currency that led to the NATO bombings that caused his overthrow and death. A beginning student in economics would understand that a strong, united, African currency would change the game in the international arena. All revolutionary Pan-Africanists know that one African currency was not Qaddafi’s idea, but his attempt to fulfill the vision of Kwame Nkrumah. These same Pan-Africanists also know that Qaddafi’s unity with Nkrumah’s vision was influenced at least in part by the A-APRP’s work with Libya, most significantly through the contributions of Kwame Ture.

There’s no question that Kwame Ture understood he would not live to see one unified socialist Africa. He knew that his job was to create revolutionary cadre who would continue to carry out that objective once his life was over. The fact that SNCC and the Black Panthers no longer exist while the A-APRP is operational on three continents and the Caribbean is testament to Kwame’s wisdom and hard work. The reality that A-APRP cadre continues to do the work from Nkrumah’s “Handbook” and that their creation was the direct result of Kwame’s careful guidance cannot be ignored. Actually, it must be stated that Kwame’s work to create strong Pan-African cadre and the A-APRP’s work to push Pan-African consciousness, along with the examples of Mugabe, Qaddafi, and many others, speaks volumes about the increasing degree of sophistication reflected in Kwame’s vision. This is a truth that provides great perspective for evaluating Kwame’s emergence from a young civil rights worker in Mississippi into a world renowned organizer in Africa with strong international contacts and trained revolutionary Pan-Africanist cadre. Could this be the actual reason for the “confidence” Joseph indicates exists within Kwame Ture that was absent from Stokely Carmichael? Today, the A-APRP is responsible for creating this Pan-African cadre in dozens of countries. They speak with one message, using English, French, Swahili, Fante, Susu, Creole, Spanish, Patwa, etc., to call for revolutionary Pan-Africanism with a socialist path. With this type of perspective regarding Kwame Ture’s work it becomes unnecessary to make the point that he “never mastered French.” Whatever languages he spoke, the cadre he helped create spawned a multitude of projects such as schools in Sierra Leone, socialist food programs in Ghana, and other political institutions throughout Africa, Europe, and the Western Hemisphere. Today there are countless books, articles, and educational materials read by thousands supporting Nkrumah and (Seku) Ture’s vision for revolutionary Pan-Africanism. This is not to mention the work to strengthen the ideological and practical commitment to Pan-Africanism that has been waged by cadre within the Democratic Party of Guinea (PDG), African Party for the Independence of Guinea-Bissau (PAIGC), Pan-African Union for Sierra Leone (PANAFU), Convention People’s Party of Ghana (CPP), Pan-African Congress of Azania, South Africa (PAC), etc. This understanding effectively negates Joseph’s continued attempts to judge the A-APRP based on “the limited number of college students that join in the U.S.” It also nullifies the suggestion that Kwame’s work in SNCC somehow outdistances the significance of his Pan-African work. It’s no stretch to say that Joseph creates a grave disservice by denying his readers a scientific understanding of Kwame’s work in Africa. In fact, this literary work is ironic in its conclusion. The reader is left with the impression that Joseph is suggesting that Kwame’s work in the U.S. was tangible whereas his work in Africa was not. The truth is its Kwame’s mass work in Africa, which is only briefly described here, that continues to have life and potential to become a true manifestation of Black Power. Pan-Africanism is Black Power expressed in its highest form. So, Kwame didn’t go astray by moving to Africa and becoming a Pan-Africanist. He in fact completed his life mission. That is the reason why it’s so disappointing that a book that started with so much promise loses credibility so rapidly and completely by presenting Kwame’s work in Africa in the same racist and uninformed fashion that we have come to expect from white leftists and bourgeois scholars.

Then, to add insult to injury, Joseph presents us with the same tired smear job against the PDG and Seku Ture. Let us first admit freely that African revolutionaries, like everyone else, have a long way to go in learning how to effectively deal with political opposition without it becoming antagonistic. Guinea under the PDG, was certainly guilty of this shortcoming as was the Libyan Jamahiriya under Qaddafi. Still, it’s not a coincidence that both those governments suffered under intense repression. It’s also no coincidence that both countries existed, under the PDG and the Jamahiriya, for decades. Guinea was politically and economically isolated because of it’s bold stance in rejecting French neo-colonialism, it’s uncompromising support for African independence and liberation through its embrace of Kwame Nkrumah (when he was overthrown by a CIA inspired coup), and its supplying a base for the guerilla movement of the PAIGC in Guinea-Bissau (and Amilcar Cabral), and it’s extension of support to guerilla movements in Angola, Mozambique, and others. A major tactic used by imperialism to isolate and punish revolutionary societies like Guinea is to deny them access to the scientific technology needed to develop resources to serve its people. Lack of technology equals poverty. The pressure this situation creates causes a great deal of stress and tension within a society. Nkrumah speaks about this in his “Letters from Conakry” book, a collection of his letters during his exile years in Guinea. He speaks to the tension within Guinea as the country was strangled out of having even the basic necessities like toilet paper. History is full of examples of how the tactic of starving people against the revolution was successful in places like Nicaragua, Angola, etc. In this environment the possibility of what Seku Ture labeled “the 5th Column” or forces whose intention is to foment disruption in the country, is an everyday reality. These are the conditions in which Seku Ture and the PDG attempted to build socialism. Of course, explaining this reality is not an attempt to excuse mistakes in Guinea, but it’s important that context is given for the conditions in the country. This way, readers can hopefully understand that the situation is much more complex than Joseph’s attempt to simply explain it away as Guinea “being less open” than the rich and imperialist U.S. Within this tense environment of siege, there is no question that the Ture regime was impacted to over react, and much of what happened at Camp Boiro during this time is probably the result of that phenomenon. But, to present this interpretation of Guinea’s years after independence without placing it within the proper context is ill responsible at best and criminal at worst. In fact, a balanced assessment of the PDG and Ture would have to conclude that considering the pressure the young country was constantly under, their accomplishments were noteworthy. If you look at Guinea today, it consistently ranks as one of the most impoverished countries in the world. They annually produce one of the highest percentages of rain fall of any country, yet electricity is a commodity in Guinea so much so that college students must go to the airport parking lot in order to study at night. It is with this understanding and context that despite the shortcomings of the PDG and Seku Ture, what they accomplished in Guinea is nothing short of miraculous. Unlike most of the world, Seku Ture understood that Guinea is a country rich in mineral resources. Today, Guinea boasts at least 60% of the world’s bauxite reserves (the mineral used to make aluminum products) along with significant reserves of diamonds and uranium. Ture refused to buckle to imperialism’s desire to exploit those resources and he educated the people there around the necessity to use Africa’s resources to advance Africa – not the wealth of European and U.S. corporations. So, even after Ture’s death, the people of Guinea understood enough of his message to resist Lasana Conte’s efforts to sell off the country’s riches. So, those resources remain today, waiting for Pan-Africanism – to develop them for future generations. It’s important to say this because imperialism is always labeling the leaders it disagrees with as dictators, but in the case of Nkrumah, Ture, or Qaddafi for that matter, they never explain why the person they are calling a dictator never attempts to exploit his country’s resources for his/her own benefit? Since that never happened with the Ture regime, the question becomes if he was such a dictator, what and how did he benefit? It’s not like the U.S. supported dictators like Pinochet, Marcos, Mobotu, Bautista, Somoza, apartheid South Africa, Israel, etc., who’s bidding for imperialism rewards and rewarded them with massive riches thus giving them clear motivation to repress the masses. Instead of exploiting his country’s resources, Ture insured that Guinea made major inroads in using whatever was available to them to make literacy a priority along with health care. Doctors from revolutionary Cuba were welcomed into the country during the Ture years to attempt to confront health epidemics and some progress was being made in these areas until the Conte regime, a classic neo-colonial government, took over in 1984. It’s a shame that Joseph never bothers to mention that repression against opposition under the Conte regime makes what happened during the Ture years look almost non-existent. It’s also interesting that during his critique against Ture, Joseph never makes an effort to explain how it is that the “corrupt, violent, and paranoid” Ture was able to stay in power for 26 years, withstanding the animosity and sabotage of every imperialist country in the world for that entire period. This is clearly a feat that would have been impossible unless Ture enjoyed massive popular support. How else does one explain the several failed imperialist backed efforts to topple the Ture government. By the same token, Conte’s regime ruled for approximately the same period with massive strikes, demonstrations, violence, and upheaval unseen during Ture’s years, in spite of the fact Conte enjoyed the full support of imperialism. This is a clear indication of the lack of popular support for his regime compared to Ture and the PDG. Could it be possible that some of this context explains why Joseph incorrectly assumes Kwame Ture was so quiet in criticizing the Ture regime? Especially since anyone who has participated in an A-APRP circle process for any reasonable period of time knows that critical analysis of the PDG, and all African revolutionary formations, is a regular aspect of political struggle within the A-APRP. In fact, a leading A-APRP cadre living and organizing with the PAIGC in Guinea-Bissau, brother Imani Na Umoja, just published a very well balanced assessment of the success of the PAIGC in maintaining its power in Guinea-Bissau in comparison to the failure of the PDG to do the same upon the death of Seku Ture. Umoja points to the lack of political education – Kwame Ture’s primary legacy - as the difference between the PDG and PAIGC. Could this be the reason for Kwame’s work with the PDG, specifically his role with the youth? Maybe if Joseph had taken the time to talk to some of the A-APRP cadre on the ground in Guinea he would have been able to understand and include this critical discussion in his biography. In fact, maybe if Joseph had taken a different approach to trying to analytically interpret Kwame Ture’s work in Africa, or more importantly the work of the A-APRP, he could have given much more insight into the true legacy of Kwame Ture. Instead, what we are left with from Joseph’s work is the very thing any of us who worked with Kwame know he absolutely abhorred. We are left with a focus on the glamour of work in the U.S. with a secondary and underdeveloped dismissal of the hard and necessary work to rebuild Africa. This is especially ironic since Kwame Ture was nothing except clear that anyone serious about Black Power would have to one day come around to Nkrumah’s analysis that “the core of the Black revolution is in Africa and until Africa is free, no African anywhere will be free.”

Joseph’s biography disregards the selfless and sincere focus of Kwame’s decision to work for Africa. His book also dismisses Kwame’s concrete contribution to advancing revolutionary Pan-Africanism, an advancement that proceeds far beyond Kwame’s work in SNCC and the Black Panthers combined. To live in the true spirit of Kwame Ture, the African intellectual, academic class one day must grasp what that legacy truly means.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed