The ponytail wearing student didn't understand Kwame's response until I took time to explain it to him. Before the "Black Power" movement in the late 60s, pretty much everything in the U.S. was status quo European, hetero-normative cultural norm. Not only was it extremely rare that anyone even challenged this in a public way, but to do so would only confirm that the challenger was someone weird and to be avoided. European, white, anglo, Christian, hetero-normative was the way everyone was supposed to be and nothing in the media, schools, churches, work places, or any other institution refuted that. This was true until the Black power movement ushered in a new era where African people began to explore who we are as a people independent of the capitalist White power system. We began to explore our African personality and identity as it relates to appearance, presentation, and ideology. This movement brought about a new level of consciousness where African people expressed that we were going to be who we are, whether America liked it or not. This idea was most radically and effectively communicated through our organizations. Most notably, the Black Panther Party, Republic of New Afrika, and Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), among others. By the 70s, the values of the Black Power movement had achieved massive institutionalization within the African community which was most effectively expressed in our push for self determination as a people. Our efforts were mirrored by other communities, including European women with the radicalization of the women's liberation movement. Then the (then titled) Gay liberation movement, etc. Whether these movements admit it or not, they were all very deeply influenced and encouraged by the Black Power movement. So, this is what Kwame meant that day at Sonoma State. The fact the young man could wear a ponytail, was because of the Black Power movement which attacked political oppression, but also attacked accepted cultural norms and appearance. All of which at the time reflected the limited value that imperialism wanted to promote. These movements, led by the Black Power movement, opened the door for a much expanded cultural expression and space which previously didn't exist. So, even something as small as how someone wears their hair is a reflection of this mass struggle for justice.

Unfortunately, most of the history of the Black Power movement is still largely untold. Today, June 17th, represents the 50th commemoration of the March against Fear in 1966 which for all intent and purposes, launched the Black Power movement of the late 60s. The march didn't start out that way. It started as the brainchild of James Meredith who was the first African admitted to the University of Mississippi. Its almost impossible to convey the sense of dread and fear that permeated the environment for those doing civil rights work in Mississippi during that time. The idea that someone would hurt and try to kill you for your desire to be able to do basic things like vote, live where you want, eat where you want, was so widespread at that time that civil rights workers lived with the trauma of death on a daily basis. This was illustrated in the fact Meredith was shot on the second day of the march. This happened within an atmosphere in Mississippi just 11 years after the brutal murder of Emmet Till. Where Medgar Evers had been gunned down in his driveway just three years earlier. Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner, murdered just two years before. Violence by the KKK and other racist elements in Mississippi and Alabama were operating with ease and impunity against the African freedom movement during this time. It is impossible for people in 2016 to understand the courage of the organizers who placed themselves in extreme danger from violent, deranged racists who had free reign to do whatever to whomever they wanted. It was in this environment that the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) led by Dr. Martin Luther King, SNCC, led by Kwame Ture, and the Congress of Racial Equality, led by Floyd McKissick, descended upon Mississippi to pledge to pick up the March against Fear from the point Meredith had been shot down. As the march picked up steam on the hot Mississippi roadway, the marchers were faced with multitudes of White Mississippians lining the shoulder of the march to openly display KKK uniforms, conferderate flags, and other racist symbols while making every effort to physically intimidate the organizers and marchers along the way. SNCC, undeterred by this terrorism, focused on its strategy to inject further militancy and African self determination into the march. For three years, SNCC had been openly advocating a change in civil rights strategy. Instead of multi-racial work, which African SNCC organizers felt exposed the contradictions of white supremacy, these organizers had been calling for sincere White organizers to organize in European/White communities while leaving the African communities to African organizers. Examples of the need for this were Whites centering the terror on their experiences, Northern Whites not always respecting the very real danger organizers, particularly African organizers, faced by disregarding the protocols set up by the organizations, and the condescending approach many Europeans displayed when engaging the Southern African communities. Consequently, the new militant leadership of SNCC symbolized by the defeat of John Lewis by Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture), planned to use this march to launch a more militant and African self determination theme. The generally held and articulated theme of civil rights marches leading up to the March against Fear was "Freedom Now." SNCC boldly sought to replace "Freedom Now" with "Black Power." Their strategy for launching the new slogan was based in having organizers branch out ahead of the march to meet with African community people along the way. As the march neared, the task these organizers had was to meet with sharecroppers and local people and have mini events and rallies around the "Black Power" theme. The ability of these courageous and determined organizers in the face of overwhelming danger, and with no cover or support, to carry out this work is overwhelming to think about. Yet, they did it. People like Dada Mukassa Ricks were assigned to engage in this fearless work and after having several events in advance of the march, Ricks reported back to SNCC late one night that the people were ready for SNCC to unleash "Black Power."

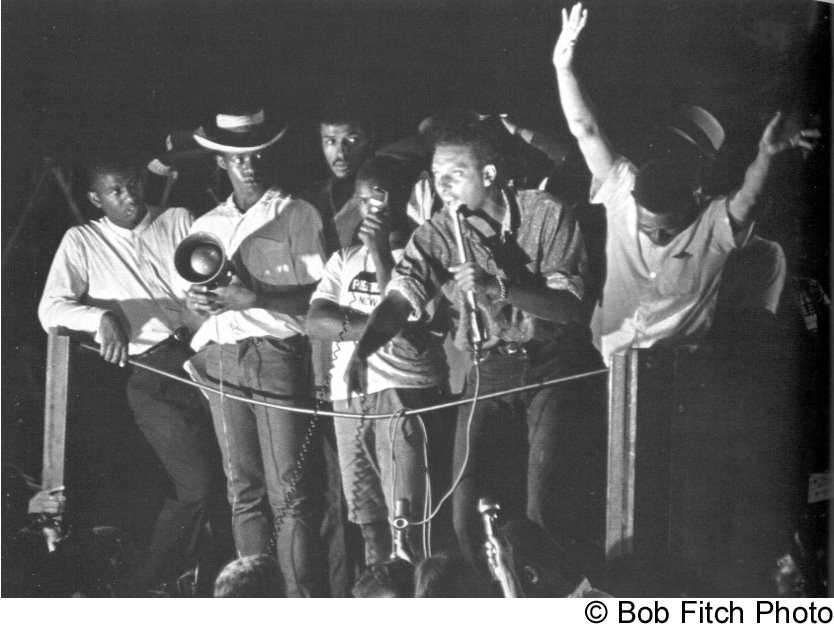

It was a balmly and dangerous night on June 17th when Kwame Ture, prompted by Ricks, delivered the "Black Power" theme to hundreds of Mississippi Africans. The people, angered by hundreds of years of the blatant legacy of violence and disrespect represented by being an African in Mississippi, responded with complete enthusiasm to the new theme. From that night forward, the tenor of the march changed. From that night forward, the tenor of the entire movement changed. From that night forward, the entire country and the world changed.

Kwame Ture became the poster child of the "Black Power" movement and much more needs to be written about the price he shouldered by taking on that task. People today have no idea how much he became public enemy number one in America. All one has to do is go to Youtube and watch his 1966 appearances on shows like "Face the Nation" or his interviews with people like Mike Wallace to get a sense of the degree of hatred and contempt America held for African people in general and this Brother in particular for this courageous stand.

Of course, three short years after 1966, Kwame Ture was living in Guinea-Conakry, never to live in the U.S. again. Still, the legacy of the "Black Power" movement and its impact on the world has yet to be measured. And the role of people like Kwame Ture, Ruby Doris Robinson, and Mukassa Ricks is also yet to be seriously acknowledged. If you are African, Indigenous, Asian, a woman, LGBTQ, or physically disabled, you owe a strong nod of respect and thanks to SNCC, Kwame Ture, Mukassa Ricks, Cleve Sellers, Ruby Doris Robinson, Ms. Fannie Lou Hamer, and all those who risked their lives for us to be able to express ourselves and live as we are today. Its also worth noting that Kwame's decision to move to Africa shouldn't be viewed as some sort of deviation from the "Black Power" path. Kwame himself articulated it clearly many times when he was engaged in one of those speaking tours up to his death in 1998. He said "in the 60s, we defined our struggle as a struggle against racism so we determined that our best weapon was to affirm that we were Black. What we learned is that our struggle wasn't just a struggle against racism, it is a struggle for power and power is land and resources. Thus, we grew to understand that our struggle is actually a struggle for control of land and resources and our land and resources are in Africa. Therefore, we grew to realize our struggle is one of achieving one unified socialist Africa!"

From Black Power forward to Pan-Africanism. Reflecting today on some brave people who sacrificed so much to make a contribution to humanity. I don't know about you, but when I feel down, I think about these people, many of them we know, many nameless, faceless. I take a moment to drink in their sacrifices. Their fears. The very real dangers they faced. And the fact many of them didn't make it. And, when I think of what they sacrificed, I immediately feel much better about whatever it is I'm consumed with.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed